When does Venture Capital make sense?

The Broader Picture: Angel Investing and Wealth Management

🖖 Welcome to Closing The Gap by JVH Ventures. After founding multiple companies, investing directly in 50+ startups and 10+ funds, we realized that a common understanding between founders, angels, and VCs is often missing.

We want to close this gap and combine perspectives from all sides.

Our goal is to look behind closed curtains and tell the honest truth.

Today we welcome Jan Voss as a guest author. Jan has tremendous experience in building family offices and managing all related investment activities. He frequently publishes highly educational content on LinkedIn and in his newsletter Cape May Wealth Weekly.

Follow along to gain insights from all directions!

Few asset classes have dominated the public discourse as much in recent years as Venture Capital (VC). During the days of low interest rates, investors tried hard to get as much capital deployed into the asset class as they could - financing capital-intensive business models ranging from electric cars to quick commerce just before they had the chance to go public via IPO or SPAC.

Three years after “peak optimism” in 2021, things look different. Many of the praised companies that ended up going public trade at a fraction of their initial valuations, or have even gone out of business. Private start-ups are struggling to maintain their lofty valuations. And even the Venture Capitalists are having a hard time raising capital for their next funds.

Investors that only started investing in VC in 2021 might be unsatisfied with performance so far, with future allocations in significant doubt. But maybe it’s exactly during these gloomy days that we should consider a closer look at VC as an investment opportunity.

Let us give you an in-depth view into what VC is:

From its fundamental basics, to its role in a portfolio, and lastly, how you can access the asset class (assuming that it is right for you).

Back to the Basics: What is Venture Capital?

The investible scope of VC is quite large, ranging from idea-stage businesses in a garage to late-stage, giant software companies. However, its key premise is usually the same: Investors in VC aim to make minority investments into young, rapidly-growing companies looking to become the next leader in their respective fields.

The companies that VCs invest in usually have little or even no revenue and high costs for technology, marketing and people, resulting in negative cash flow. VCs solve this issue of negative cash flow by providing growth capital, allowing those companies to reach the next step of their growth journey. This growth capital is typically provided as equity, meaning that with each financing round they provide, VCs acquire a stake in the underlying business. They hope to monetize this stake at a later point in time, either by selling their stake partially (a “secondary transaction”, where just the VC might sell a stake), entirely (for example through a sale of the entire company to a strategic or financial investor), or by taking the company public through an Initial Public Offering (IPO).

While the time to exit might vary depending on the “stage” of the underlying portfolio companies (i.e. how mature the company is, so just founded or close to IPO), VC is for the most part a long-term game. If you are an early stage investor, it might take five, ten or even 15 years until your portfolio companies are sold - in particular, if the company does well, in which case VCs are usually advised to let their winners ride rather than to sell them early. Accordingly, even among other illiquid asset classes such as private equity or hedge funds, VC is extremely illiquid. Any investor in the asset class should expect a single fund to pay back its invested capital 8 to 10 years after you made the investment, with the actual returns more likely to be distributed somewhere between years 10 and 15.

Last, but not least, probably the most important point about investments in early-stage startups: They face a significant risk of total loss of capital. Nascent technologies might not find “product-market-fit”, hard-working teams might fall apart over personal issues, or companies might simply run out of money. Accordingly, most start-ups fail, resulting in partial or full write-off of a VC’s investment. This, however, is offset by the success of the few substantial winners: VCs that invested early into companies such as Uber or Airbnb generated double-, if not triple-digit multiples on their invested capital.

This logic is called the “Power Law”, in which a small percentage of start-ups generate the lion’s share within a VC portfolio. At JVH Ventures, around 8% of the best companies return more than the rest combined. However, this might be a rather large share of winning companies on average, as VCs normally calculate with 1-2% of funds returning outlier startups in their portfolios' construction. JVH Ventures might not be representative here, as they both have lower rate of losses and the portfolio is still rather young.

Accordingly, it is critical to remember that in VC, a substantial portion of direct investments fail or generate just minor returns - making it necessary for investors to construct a sufficiently diversified portfolio.

Feel free to dive deeper into the mechanics of venture portfolio construction in this series here:

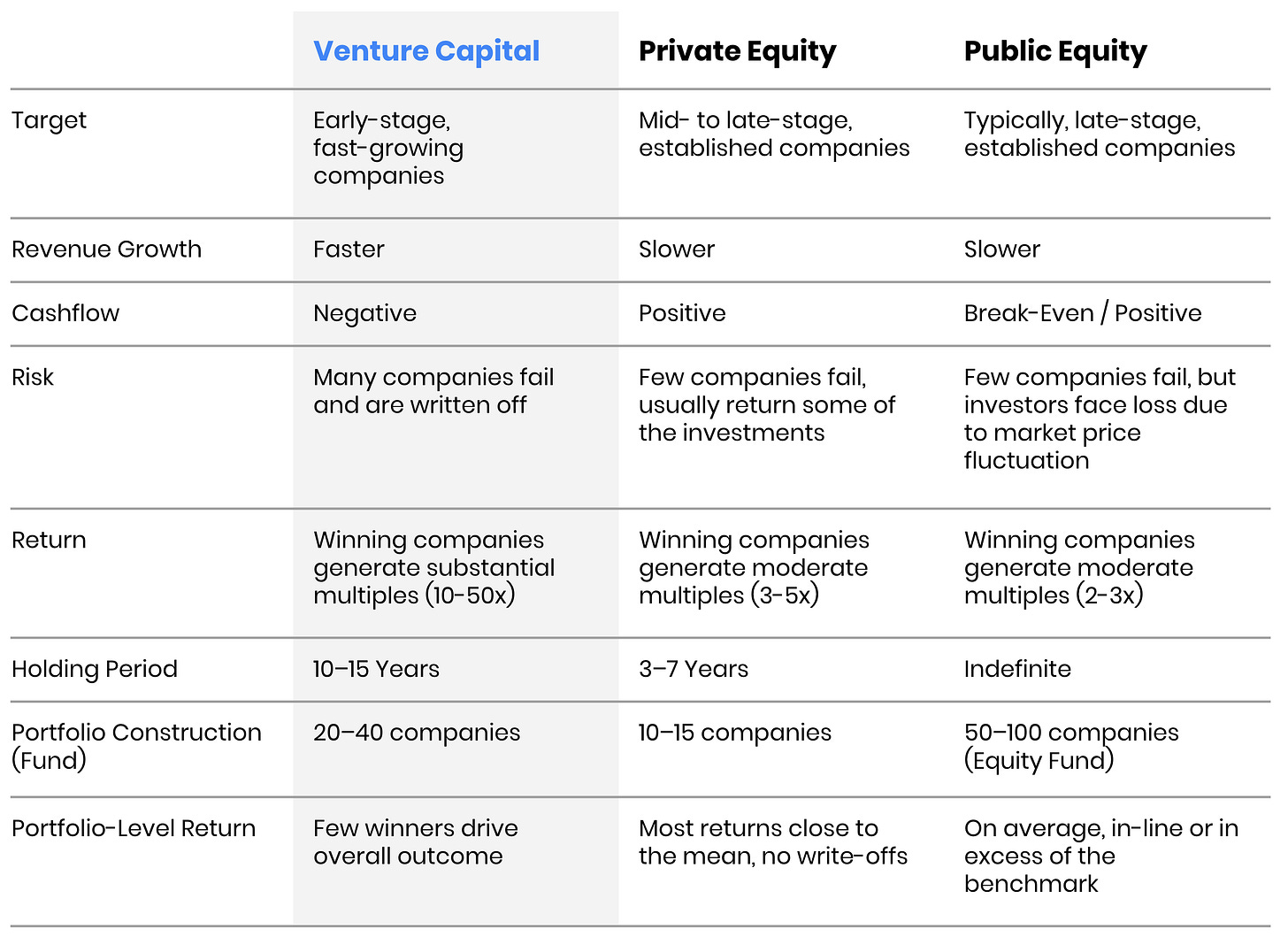

For better understanding, let’s put this into comparison:

The Power Law: Understanding Venture Capital’s Key Return Driver

Investors should be particularly mindful of how the potential return outcomes affect a VC or PE fund’s portfolio construction. Let’s first look at Private Equity: For worse-performing deals, a PE fund would always try to ensure that this deal returns it invested capital, i.e. a 1x multiple. For well-performing deals, the target multiple is lower than in VC, usually ranging around 3-5x. However, most deals are expected to come in somewhere between those two figures, typically between 1,5x and 3x. Given this tighter return distribution, PE funds can build concentrated portfolios of 10–15 companies without running the risk of building a loss-making portfolio at fund level.

In VC, things are very different. As we explained, a significant number of start-ups fail to produce relevant returns. But how do these company-level figures translate to the portfolio level? To do so, we can look at the data shared by David Clark of the Venture Fund of Fund VenCap. Let’s first again look at the worse-performing deals. In the case of VenCap, 53% of their 11,350 (indirect) portfolio companies failed to generate returns sufficient to return invested capital (and VenCap, which has been around since 1986, is likely picking above-average fund managers, which might have a positive effect on their loss rate.) Before even diving into the return expectations for well-performing deals, we can already see the Power Law in action: To generate a fund-level multiple of 3x or better before fees, the remaining 49% of deals need to generate significant returns to offset deals on which VCs lose money.

What does significant mean? We can again see this in VenCap’s data. In their funds, 19% returned between 1 and 2x, 16% returned between 2x and 5x, and 12% of deals returned more than 5x of invested capital. If we want to achieve a 3x multiple before fees, we can use simple math to calculate what average returns the “Above 5x” deals need to generate:

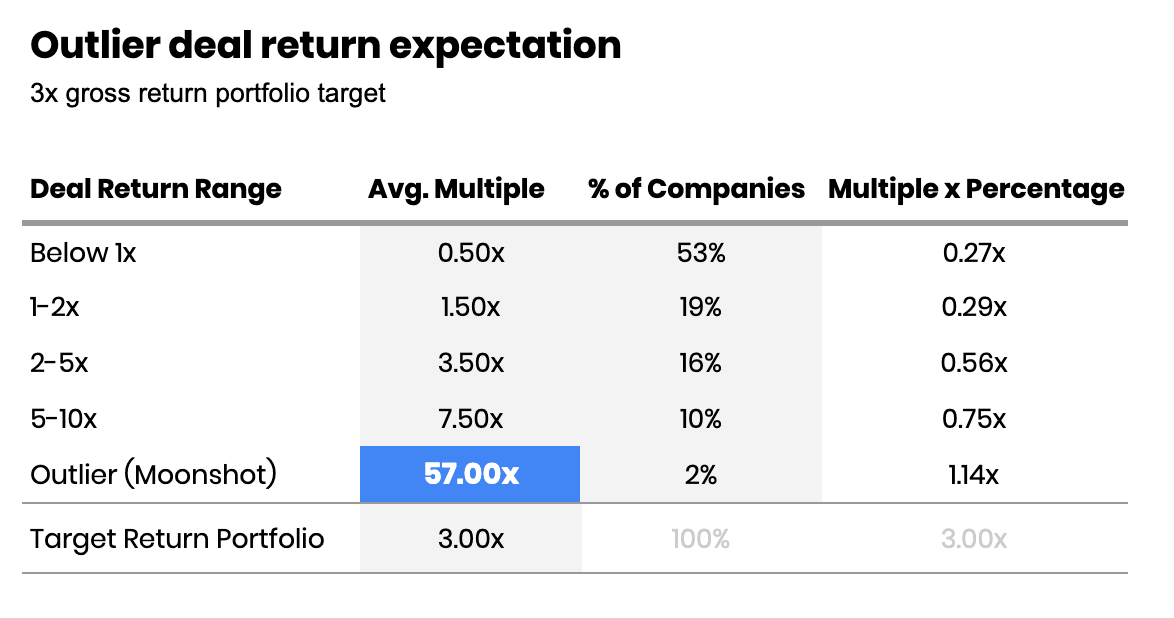

Return Range and % of Companies based on VenCap Data as outlined above. Avg. Multiple estimated as average multiple within the mentioned range. Target Return of 3.00x based on typical Target Multiple of a VC Portfolio (before portfolio-level fees), i.e. a 3.00x “gross return”Hence, using Vencap’s figures and our target return of 3x (before fees), the remaining 12% of the fund would need to generate an average return of ~15,75x to reach its 3x target return.

With a typical VC fund consisting of 30-40 portfolio companies, that would mean that we have ~3-4 portfolio companies with this double-digit multiple. Realistically, however, the distribution is even more extreme, where just one portfolio company (~2% to 2.5% of the fund) drives a substantial part of the fund’s performance. This is also consistent with the return expectations of a VC fund, which tries to size (and value) its investments in a way so that a single deal, if it’s a home run success, can return the entire fund.

We can extend our prior table, and once again use simple math to complete the calculation:

Return Range and % of Companies based on VenCap Data as outlined above. Avg. Multiple estimated as average multiple within the mentioned range. Target Return of 3.00x based on typical Target Multiple of a VC Portfolio (before portfolio-level fees), i.e. a 3.00x “gross return”. Breakdown of prior “Above 5x” bucket (12%) into 10% of 5-10x returns and 2% “Moonshots”.In other words, if we assume that 10% out of the 12% in VenCap’s “above 5x” multiple achieved an average return of 7,5x, that would mean that our remaining single deal (i.e. 2% of the fund) would need to achieve a staggering 57x (!) return for us to achieve our performance goal of 3x.

This outlier-driven nature of VC has a profound impact on the distribution of VC fund outcomes, and accordingly, the performance of VC in investor portfolios. Some outliers can drive significant returns, even in excess of this hypothetical 57x multiple. But likewise, the absence of an outlier return means that the fund will struggle to achieve its desired returns.

To understand how this impacts you as an investor, let’s take a look at what we call return dispersion, and the importance of what we call manager selection.

Manager Selection: Or, how to capitalize on return dispersion

Even if this is your first foray into VC investing, you hopefully have built some prior experience investing in public markets. In public markets, you might’ve actually encountered so-called return dispersion before: It is the distribution of returns of a given asset class (say, US Equities) relative to its average. Some active fund managers might outperform (i.e. they achieve performance in excess of the S&P 500 (or another US Equity benchmark), while others might underperform. The larger the difference between the outperforming funds and the underperforming funds, the larger the so-called return dispersion.

So why should you care about return dispersion? Because VC is the asset class that has, by far, the largest return dispersion, i.e. the largest span between well-performing and underperforming funds.

While the average VC fund achieved decent returns relative to the NASDAQ (according to Cambridge Associates, a 16.9% return over the last 10 years ending in September 2023, relative to 14.9% for the NASDAQ) (Source), there is a good chance your return was far away from that average. According to an analysis by CAIS (Source) from November 2022, using IRRs rather than annualized returns, the median VC fund generated a return of 8.2%. However, as we mentioned before, VC return dispersion is massive: top-quartile funds generated returns between 17% p.a. (decent!) to 79% p.a. (mind blowing), while bottom-quartile funds saw returns between 0.3% (at least it’s positive) to -22.4% p.a. (terrible).

Assuming you first start your VC investing journey by investing in VC funds rather than investing into companies directly, that dispersion is exactly the reason why you should care about Manager Selection. Manager Selection, as the name says, is the skill (and art) of finding managers of which you would hope that they find themselves in the top quartile of managers - or at least, above average.

However, the rules of VC, and its massive return dispersion, also apply for an investor looking to make direct investments in the asset class: You need to be aware that your outcomes can vary significantly. And unlike for example liquid asset classes, where your underperformance might be a single-digit percentage, underperformance in VC can mean significant underperformance, or perhaps even total loss of invested capital.

While for now we focus on the question whether to invest in VC funds, we will dive deeper into direct vs. fund investments in the future!

The role of Venture Capital in a Diversified Portfolio

Before we answer this question, let’s first point out what we deem to be the key benefits of VC as an asset class.

(1) VC allows an investor to invest in disruptive business models and technologies before they move into the mainstream.

If we look back at some of the big venture-backed companies of the last 10–15 years, we can see how the mainstream initially didn’t think their business model could succeed given that it was so novel - think companies like Uber, Airbnb or Coinbase. Ideally, this focus on cutting-edge technology translates into superior returns. However, for many investors, investing into VC and thus innovative business models can be a reward in itself: They don’t just want to see their capital invested into a diversified, impersonal equity ETF, but want to see directly how their capital can generate a positive impact in the world.

(2) VC is a very long-term oriented asset class.

As we mentioned above, the long holding period is a result of a fund’s winners remaining in the portfolio to compound value until an eventual exit late in their fund lifetime. The magic word here is compounding: While average IRRs (leaving aside dispersion for now) are actually not that different between VC and private equity, VC ends up having higher fund-level multiples given the longer average holding period. If you are an investor that isn’t dependent on distributions and/or can invest in this part of your portfolio for a long time, there are few other asset classes allowing such long-term compounding without reinvestment.

(3) VC, both at portfolio and fund level, has significant performance dispersion, which rewards investors skilled at manager selection.

At portfolio level, many companies are written off while few winners drive the fund-level returns. Given the risk at the venture stage, constructing the portfolio to aim for outlier returns is a necessity. The same applies at fund level: Average and below-average VC fund returns are often disappointing, barely achieving the returns of public comparable indices like the benchmark while also locking up investor capital for a significant amount of time, while top-quartile VC funds might be generating some of the best IRRs an investor can access across various asset classes. If you manage to continuously pick above-average, or even top-quartile funds, there are few other asset classes that can generate such substantial, long-term compounding returns. However, this is not a trivial task - and accessing top-quartile managers can be difficult, especially for smaller investors.

So with that in mind, how does Venture Capital fit into a diversified portfolio?

We should first consider the risks of an asset class. In the case of VC, those risks are illiquidity and performance dispersion.

Illiquidity tends to be the key consideration, even for those that might have manager selection skills. One VC fund by itself might take ten years to return its invested capital. If you build a portfolio of funds, where early distributions are used to fund capital calls of other funds, this break-even point moves even further into the future. While selling stakes in a VC fund isn’t impossible, it can be time-consuming and usually comes with substantial discounts to the fund’s underlying value. Said differently: If you aren’t willing to stay invested in VC for 15 years, or expect that you will require some of that invested capital back earlier than that, VC is not the right investment for you.

But even if you are willing to hold onto your investments for that long, VC might still not be the best choice, given the aforementioned performance dispersion. I personally like to refer to the aforementioned figures by Cambridge Associates: As we pointed out, Cambridge’s US VC Index returned 16.89% p.a. over the last 10 years, roughly 2% higher than the NASDAQ. But it wasn’t always this way: If we look at a 15-year period, VC actually underperformed NASDAQ by 1.6% p.a., and was just 0.5% ahead of the index over a 20-year period. And let’s not forget that your NASDAQ ETF can be sold daily, whereas your VC fund is extremely illiquid. Accordingly, you need to ask yourself whether this level of outperformance of the average is worth the illiquidity and the risk of underperformance - and most importantly, if you think you are selecting and accessing funds that can outperform. If the question to this answer is no, we’d advise to best stay away.

So in which case does VC make sense?

From our point of view, if you are willing and able to stay invested in the asset class over long periods of time, and if you have the necessary skills and access to pick above-average managers. If that is the case, we’d even go as far to say that there is no better asset class to achieve attractive long-term returns than VC.

The next-best option, Private Equity, has similar average returns but much less performance dispersion (i.e. providing comparably less reward for good manager selection), and has shorter holding periods, which reduce the positive impact of compounding and bring a higher reinvestment risk.

We would like to thank Jan Voss for writing this article! Learn more about him below.

Jan is the Managing Director of Cape May Wealth, a Berlin-based wealth advisory firm specialized in supporting entrepreneurs and their family offices. He began his career at Goldman Sachs before moving to Berlin to join the family office of one of Germany's most famous entrepreneurs.

Previously to Cape May Wealth, he was the Head of Family Office at BLN Capital, a Berlin-based family office. He regularly publishes content on topics such as asset allocation, wealth management, and alternative investments on LinkedIn and through his newsletter Cape May Wealth Weekly.

Thank you for reading! If you liked, feel free to share it with someone else who could profit from it - angels, founders, VCs, anyone :)

PS: We are always happy to answer your questions or take on topics you want to hear about to close the gap! Just let us know.